Throughout history, many people had agreed upon the fact that New York’s skyscrapers are the clearest depiction of the notion of what is modern. However, one of the greatest architects of the XX century, Le Corbusier, used to think otherwise, and would constantly call the city of New York a beautiful catastrophe. Any New Yorker knew what the famous architect wanted to say: he hated the contrasts within the city, its society, the class inequality, and, more importantly, he wanted to shorten the distance between the streets and the towers. Le Corbusier would conceive the city of New York as a feasible yet imperfect utopia. Back then, the New York citizens did no pay much attention to Le Corbusier’s thoughts, and they continue without doing so. The last and the present century have been eras where a certain number of utopian proposals have taken place. Whether drawn, projected, discussed and or even built, these proposals have demonstrated that there is no such thing as the ideal and perfect city.

When planners committed themselves to shaping the existent and alive — to some extent — cities into utopias, they ended up destroying them. Apparently, just like plants, cities and individuals require some sort of substrate for them to grow, yet, the greatest minds of the recent culture have thought otherwise. They firmly conceived the concept of art as something capable of enhancing and transforming people, especially the architecture, since is the one that is directly linked with individuals: it is the art where humans live in.

The rational design would create, as a result of its implementation, rational societies. Many architects of that time faced the upcoming years with optimism: the modern movement. Back then, the idea that if there were a proper architecture, the life of individuals would be inexorably much better. However, the architects of this modern approach were not the first ones who realized the flaws within their visionary idea: Da Vinci had previously concluded the impossibility of establishing an utopia as the perfect city. As Kenneth Slaught has previously mentioned, the process of design has suffered lots of changes — for the better.

During the early 20’s Le Corbusier had already found out that many cities around the world were on the verge of an imminent implosion. Just like Da Vinci, the Swiss architect realized that modernist theories had resulted in poor design and a highly inadequate housing procedures and constructions besides the poorly efficient transportation. He then reconfigured the modernist approach by studying the underlying problems within the movement and suggesting possible solutions to these kinds of issues. He went on to inspire and influence a new generation of architects and planners who would then rethink what the initial modernist theory had suggested in order to prevent what Le Corbusier had foreseen and to improve the quality of life of every individual.

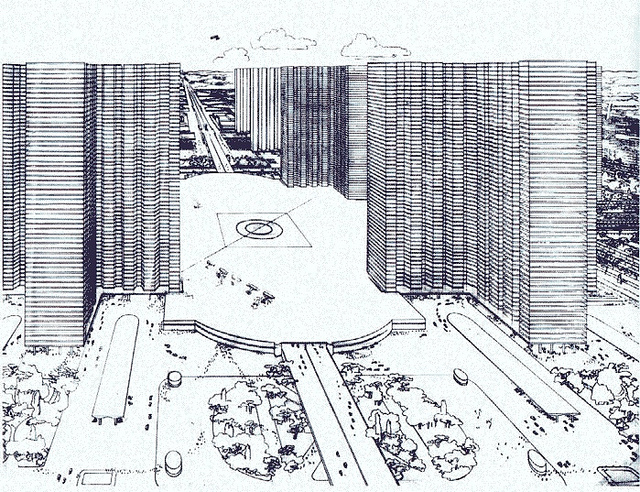

Le Corbusier firmly believed in the notion that the concept of modern cities could only be feasible and could only function upon the substrate of right and straight order, which was his basis for developing several planning schemes using four principles: the conjunction of the center of the cities, augmentation of the density, enlargement of the means of transportation and circulation, and increment in the existent number of open spaces — which can be seen in his planning for Voisin, France.

His plans for sustainable and ordered modern cities included a detailed analysis of three major urban issues and factors: housing, open spaces, and roads. Le Corbusier believed that roads should be established with minimum crossings. Consequently, the separation of the existent forms of traffic would make them inhabitable. He suggested skyscrapers for commotion purposes only, surrounded by extensive open spaces. Le Corbusier’s ideal of a modern city included on average a high percentage of open spaces, resembling a big park surrounded by buildings.

His ideas, resumed in five points, were used to conceive the idea of how to live in nowadays industrialized world. He suggested, that buildings should be at all cost lifted over pilots as a way to enhance the transportation as the ground floor of any construction, just like the street, belongs to pedestrians and vehicles. Readers can realize the application of this principle every time they see houses lifted on pilotis that allow the vehicle’s movement or the green extension continuity. As the second principle, the architect suggested that the designing of any ground plan should be free in style and from structural conditioning so that partitions can be established in any way, which was somehow connected with his third concept that suggested that facades should be apart from the structure. The façade, and as his fourth suggestion, could be cut in its entire length to allow the room to be lit equally and, last but not least, Le Corbusier firmly believed that any type of building or housing should give back the space it takes up from the ground, which is why he suggested garden roofs as way of replacing it.